I would say this post is back by popular demand, but I’d be lying. No one has demanded it. I post it because it’s almost Halloween, and because I had fun writing it way back when, and because I want to.

To learn why I wrote it, read on. If you don’t care why I wrote it, skip the next part, but the poem will be easier to understand if you just keep reading.

*****

Why? Because–A friend called to confirm that David and I would meet her and her husband the next day for the Edgar Allan Poe exhibit at the Harry Ransom Center. She mentioned that her house was being leveled for the second time in three years*: “There are thirteen men under my house.”

I hooked up Edgar Allan Poe with the number thirteen and house with Usher and wrote the following verse.

Note: Tuck and Abby are my friends’ dogs.

Another note: Maven means expert. I looked it up to make sure.

*

THE MAVEN

To G. and M. in celebration

of their tenth trimester

of home improvement,

with affection.

Forgive me for making

mirth of melancholy.

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered weak and weary

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore,

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a rapping,

As of someone gently tapping, tapping at my chamber floor.

“‘Tis some armadillo,” said I, “tapping at my chamber floor,

Only this, and nothing more.”

Ah, distinctly I remember it was in the dry September,

And my house was sinking southward, lower than my bowling score,

Pier and beam and blocks of concrete, quiet as Deuteron’my’s cat feet,

Drooping like an unstarched bedsheet toward the planet’s molten core.

“That poor armadillo,” thought I, “choosing my house to explore.

He’ll squash like an accordion door.”

“Tuck,” I cried, “and Abby, come here! If my sanity you hold dear,

Go and get that armadillo, on him all your rancor pour.

While he’s bumping and a-thumping, give his rear a royal whumping,

Send him hence with head a-lumping, for this noise do I abhor.

Dasypus novemcinctus is not a beast I can ignore

Clumping ‘neath my chamber floor.”

While they stood there prancing, fretting, I imparted one last petting,

Loosed their leashes and cried “Havoc!” and let slip the dogs of war.

As they flew out, charged with venom, I pulled close my robe of denim.

“They will find him at a minimum,” I said, “and surely more,

Give him such a mighty whacking he’ll renounce forevermore

Lumbering ‘neath my chamber floor.”

But to my surprise and wonder, dogs came flying back like thunder.

“That’s no armadillo milling underneath your chamber floor.

Just a man with rule and level, seems engaged in mindless revel,

Crawling round. The wretched devil is someone we’ve seen before,

Measuring once and measuring twice and measuring thrice. We said, ‘Señor,

Get thee out or thee’s done for.'”

“Zounds!” I shouted, turning scarlet. “What is this, some vill’nous varlet

Who has come to torment me with mem’ries of my tilting floor?”

Fixing myself at my station by my floundering foundation,

Held I up the quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore.

“Out, you cad!” I said, “or else prepare to sleep beneath my floor,

Nameless there forevermore.”

Ere my words had ceased resounding, with their echo still surrounding,

Crawled he out, saluted, and spoke words that chilled my very core.

“I been down there with my level, and those piers got quite a bevel.

It’s a case of major evolution: totter, tilt galore.

Gotta fix it right away, ma’am, ‘less you want your chamber floor

At a slant forevermore.”

At his words there came a pounding and a dozen men came bounding

From his pickup, and they dropped and disappeared beneath my floor.

And they carried beam and hammer and observed no rules of grammar,

And the air was filled with clamor and a clanging I deplore.

“Take thy beam and take thy level and thy failing Apgar score

And begone forevermore.”

But they would not heed my prayer, and their braying filled the air,

And it filled me with despair, this brouhaha that I deplore.

“Fiend!” I said. “If you had breeding, you would listen to my pleading,

For I feel my mind seceding from its sane and sober core,

And my house shall fall like Usher.” Said the leader of the corps,

“Lady, you got no rapport.”

“How long,” shrieked I then in horror, “like an ominous elm borer,

Like a squirrely acorn storer will you lurk beneath my floor?

Prophesy!” I cried, undaunted by the chutzpah that he flaunted,

And the expertise he vaunted. “Tell me, tell me, how much more?”

But he strutted and he swaggered like a man who knows the score.

Quoth the maven, “Evermore.”

He went off to join his legion in my house’s nether region

While my dogs looked on in sorrow at that dubious guarantor.

Then withdrawing from this vassal with his temperament so facile

I went back into my castle and I locked my chamber door.

“On the morrow, they’ll not leave me, but will lodge beneath my floor

Winter, spring, forevermore.”

So the hammering and the clamoring and the yapping, yawping yammering

And the shrieking, squawking stammering still are sounding ‘neath my floor.

And I sit here sullen, slumping in my chair, and dream the thumping

And the armadillo’s bumping is a sound I could adore.

For those soles of boots from out the crawlspace ‘neath my chamber floor

Shall be lifted—Nevermore!

*

The reason the house was leveled twice in three years is a story in itself, not to be told here.

Three writers with ties to Texas Wesleyan read from their works. Dr. Jeffrey DeLotto read from his novel

Three writers with ties to Texas Wesleyan read from their works. Dr. Jeffrey DeLotto read from his novel

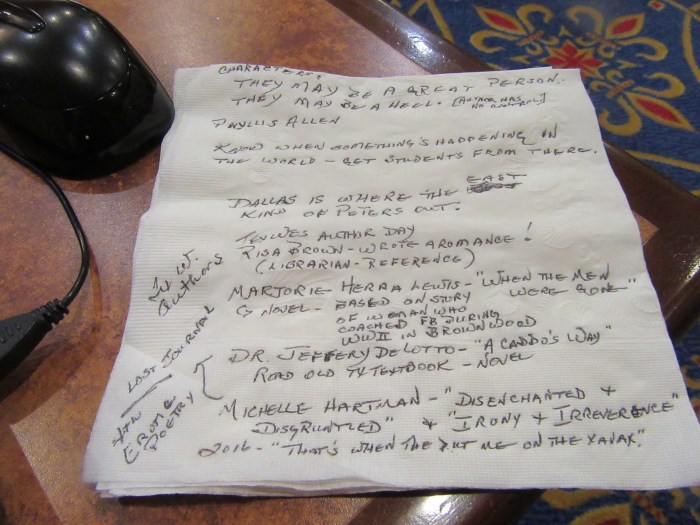

Citations: Here’s a picture of my notes. I like to get things right, and since I had nothing to write on but a napkin . . .

Citations: Here’s a picture of my notes. I like to get things right, and since I had nothing to write on but a napkin . . . Lester Hessenpfeffer awakens on a bath rug stuffed into the corner of a gigantic cage and stares into the open eyes of the bull mastiff. The dog wags his tail once, twice, and Lester feels his chest tighten with joy. Just before he fell asleep, he’d been preparing a speech for the dog’s owners about how he’d done his best, how he’d tried everything, but . . . Samson had ingested a few Legos the day before, which the owners’ great-grandchildren had left lying about. One had perforated his intestine. By the time he was brought to Lester’s clinic, the dog was in shock and the prospects for saving him were almost nil. Lester had slept in the cage with him to provide comfort not so much for the dog as to himself. He’d known Samson since he was a puppy, and he was very fond of the owners, an elderly couple who thought Samson hung the moon. They’d wanted to spend the night at the clinic, but after Lester told them he’d be literally right beside the dog, they reluctantly went home. Lester had hoped they’d get some sleep, so that they could more easily bear the news he was pretty certain he’d have to deliver in the morning. This is always the worst part of his job, telling people their pet has died. Sometimes they know it, at least empirically; on more than one occasion someone has brought a dead animal into the office hoping against hope that Lester can revive it. And when he can’t, he must say those awful words: I’m so sorry. He’s noticed a certain posture many people assume on hearing those words. They step back and cross their arms, as though guarding themselves against any more pain, or as though holding on more time the animal they loved as truly as any other family member, if not more. Oftentimes, they nod, too, their heads saying yes to what their hearts cannot accept.

Lester Hessenpfeffer awakens on a bath rug stuffed into the corner of a gigantic cage and stares into the open eyes of the bull mastiff. The dog wags his tail once, twice, and Lester feels his chest tighten with joy. Just before he fell asleep, he’d been preparing a speech for the dog’s owners about how he’d done his best, how he’d tried everything, but . . . Samson had ingested a few Legos the day before, which the owners’ great-grandchildren had left lying about. One had perforated his intestine. By the time he was brought to Lester’s clinic, the dog was in shock and the prospects for saving him were almost nil. Lester had slept in the cage with him to provide comfort not so much for the dog as to himself. He’d known Samson since he was a puppy, and he was very fond of the owners, an elderly couple who thought Samson hung the moon. They’d wanted to spend the night at the clinic, but after Lester told them he’d be literally right beside the dog, they reluctantly went home. Lester had hoped they’d get some sleep, so that they could more easily bear the news he was pretty certain he’d have to deliver in the morning. This is always the worst part of his job, telling people their pet has died. Sometimes they know it, at least empirically; on more than one occasion someone has brought a dead animal into the office hoping against hope that Lester can revive it. And when he can’t, he must say those awful words: I’m so sorry. He’s noticed a certain posture many people assume on hearing those words. They step back and cross their arms, as though guarding themselves against any more pain, or as though holding on more time the animal they loved as truly as any other family member, if not more. Oftentimes, they nod, too, their heads saying yes to what their hearts cannot accept.