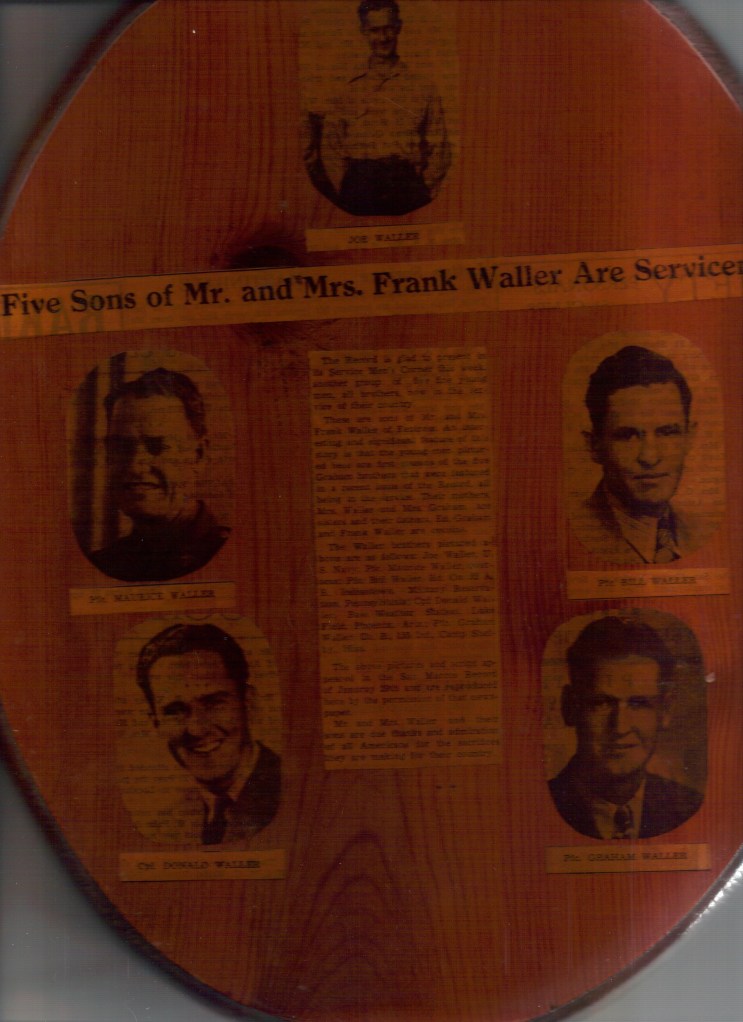

My father, Billie Waller, volunteered for the U.S. Army early in 1941.

He served in World War II in Northern Europe. He drove onto Omaha Beach on June 19th, 1944.

He refused all promotion.

He said the coldest winter he’d ever known was the one he spent in Cologne.

He repeatedly fell for a prank played by fellow soldiers: Knowing he had lost his sense of hearing, they would signal that a bomber was approaching and run; then, when he dived into a foxhole, they laughed. When Major Yarborough, the officer he drove for, finally happened to see, and so realized that one man under his command couldn’t hear and others were endangering him, he got the one out of harm’s way and disciplined the rest (how the Major did the latter, I don’t know).

My father was sent from the front lines in Germany to spend the last months of the war as an ambulatory patient in a Paris hospital, deaf from bomb concussion.

He arrived in Dallas, where my mother was living and working, before dawn on October 23, 1945, and handed his hearing aids to his mother-in-law with instructions not to tell my mother. Mother-in-law told. After several days of yelling to make herself heard, my mother told him to get the hearing aids and wear them. He’d been afraid she wouldn’t love a deaf husband.

He gave my mother his uniforms and said, “Get rid of these.”

He kept his dog tags, some foreign coins, and a cigar holder given him by a Belgian farmer.

He delighted his mother-in-law by saying, “Oh la la!”

He had dinner ready every night when my mother got home from work. He specialized in chocolate pies topped by a mountain of meringue. Removing one from the oven, he flipped it upside-down onto the oven door and had to serve it as a pudding.

He was turned down for a job in warehousing because he was deaf (ironic, since he later worked in supply in Air Force Civil Service). He got a job in a toy store, where he sold a tricycle to a couple with a little boy. After the sale, he learned the trike was a demo, the only one the store had, and the only one it was likely to get in the foreseeable future. Having been overseas, he wasn’t familiar with shortages on the homefront. (My mother said if he had known, he’d have been tempted to sell it anyway, because he believed little boys who wanted tricycles shouldn’t have to wait.)

On May 1, his birthday, he took the day off and spent it with Yarborough (no longer Major) in Fort Worth. When he didn’t return timely for the birthday dinner she’d cooked, complete with chocolate cake with fudge icing, my mother cried and cried. She realized later, she said, laughing, that at that point, my dad had lived with Yarborough a lot longer than he’d lived with her, and that the two men probably had more in common.

After six months in Dallas, he achieved the dream that had kept him going throughout his years away. If my mother had worked for another six months, she would have had reinstatement privileges with Civil Service, but she didn’t hesitate. The San Marcos River was the only place he wanted to be, or would ever want to be. They moved to Fentress.

My mother said that of all the men she knew who served in World War II, he was the least changed. He came home and was again just Bill, with the quiet, dry sense of humor and the twinkle in his blue eyes. He put the war behind him and went on with life.

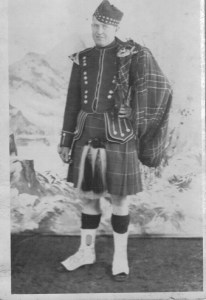

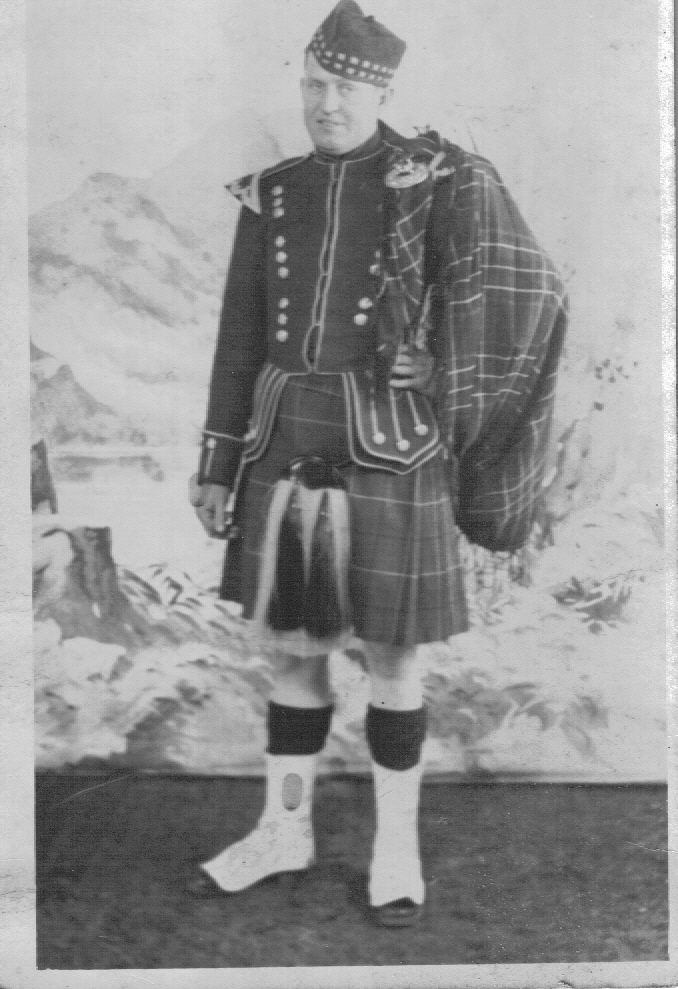

When he spoke of his service, he confined himself to people he’d known and the lighter side of daily life. While stationed in Scotland he and some friends had their pictures taken in traditional dress. He said one of the men, when changing back into uniform, forgot to take off the socks, and got back to the base wearing the photographer’s argyles.

When he spoke of his service, he confined himself to people he’d known and the lighter side of daily life. While stationed in Scotland he and some friends had their pictures taken in traditional dress. He said one of the men, when changing back into uniform, forgot to take off the socks, and got back to the base wearing the photographer’s argyles.

He made a few observations: He respected General Omar Bradley but had a low opinion of Patton.

But he didn’t share stories of combat. He’d written my mother, “I’ve seen things you wouldn’t believe. I’ll tell you when I get home.” He never told.

Two remarks he made years later suggest why:

My mother told me about the first: When his brother Donald and others were talking about looting that occurred on the battlefield, my father, who’d been silent, suddenly said, “I’ve seen them cut off fingers to get rings.”

He made the second comment in my presence: My uncle’s stepson, who had served in the military but seen no combat, was looking forward to watching the movie Anzio on television. He said, “I can’t imagine hitting the beach and running into enemy fire like that.” My father replied, “There’s nowhere else to go.”

Such memories aren’t conducive to going on with life.

In 1964, when President Eisenhower’s memoir of D-Day and the Invasion was published serially in the San Antonio newspaper, he read it. Occasionally, he said, “No, that’s not quite right . . .” or, “He’s forgotten about . . .”

The one thing he couldn’t leave in the past was his deafness. The hearing aid didn’t filter out ambient noise, and he often walked out of gatherings–family get-togethers, wedding receptions, church dinners–that he would otherwise have enjoyed. He left Civil Service because his job at the time required taking sensitive, detailed information over the telephone, and he was afraid of making a mistake, which could have cost lives.

In 1967 and 1968, surgery at the VA hospital in Houston restored hearing in both of his ears and allowed him to lead a normal life.

In the summer of 1981, he finally expressed a desire to attend a reunion of the men he’d served with. An angina attack sent him to the hospital that weekend instead. He didn’t get another opportunity to see them again.

***

The cigar holder lived–and still lives–in the silver chest. I’ve known about it practically all my life and occasionally took it out and examined it when I was a child–but it took decades for me to realize its meaning. The farmer didn’t give a cigar holder to just some young man passing through; he gave it to an American GI, one among thousands he’d waited and hoped for, who was risking his life to free the Belgian people, and all of Europe, from the tyranny of Nazi Germany. The cigar holder represented gratitude, and more. In my mind’s eye, I see my my father and that farmer talking about the weather and how the crops were doing–if any arable land hadn’t been overrun by bootsoles and tanks. They’d have been speaking different languages, of course, but the language of farmers, and of friendship, is universal. And since my father was involved, they’d also have been laughing.

The cigar holder lived–and still lives–in the silver chest. I’ve known about it practically all my life and occasionally took it out and examined it when I was a child–but it took decades for me to realize its meaning. The farmer didn’t give a cigar holder to just some young man passing through; he gave it to an American GI, one among thousands he’d waited and hoped for, who was risking his life to free the Belgian people, and all of Europe, from the tyranny of Nazi Germany. The cigar holder represented gratitude, and more. In my mind’s eye, I see my my father and that farmer talking about the weather and how the crops were doing–if any arable land hadn’t been overrun by bootsoles and tanks. They’d have been speaking different languages, of course, but the language of farmers, and of friendship, is universal. And since my father was involved, they’d also have been laughing.

***

Two 50-centime Belgian coins.

Left, the profile of King Leopold II, dated 1888 or 1886.

Left, the profile of King Leopold II, dated 1888 or 1886.

Right, the profile of King Albert, date obscured by tarnish. Albert succeeded Leopold in 1909.

A dose of silver polish and elbow grease and more will be revealed.

![Bill%20Waller%20in%20kilt%2C%20circa%201943-1944[1]](https://kathywaller1.com/wp-content/uploads/2010/11/bill20waller20in20kilt2c20circa201943-19441.jpg?w=205)